ŌģĀ. Introduction

Dilaceration is defined as an angulation or a sharp bend/curve in the root or the crown portion of a formed tooth[

1]. It typically occurs as a result of trauma (such as intrusion) to the deciduous predecessors and results in non axial displacement of the already formed hard tissue portion of the developing tooth[

2]. The prevalence of dilaceration constitutes 3% of all injuries in developing teeth[

3]. Dilacerations generally involve central incisors; most often maxillary incisors rather than their mandibular counterparts[

4,

5]. The clinical features of dilaceration include non-eruption of the successive tooth or prolonged retention of the deciduous predecessor tooth[

6].

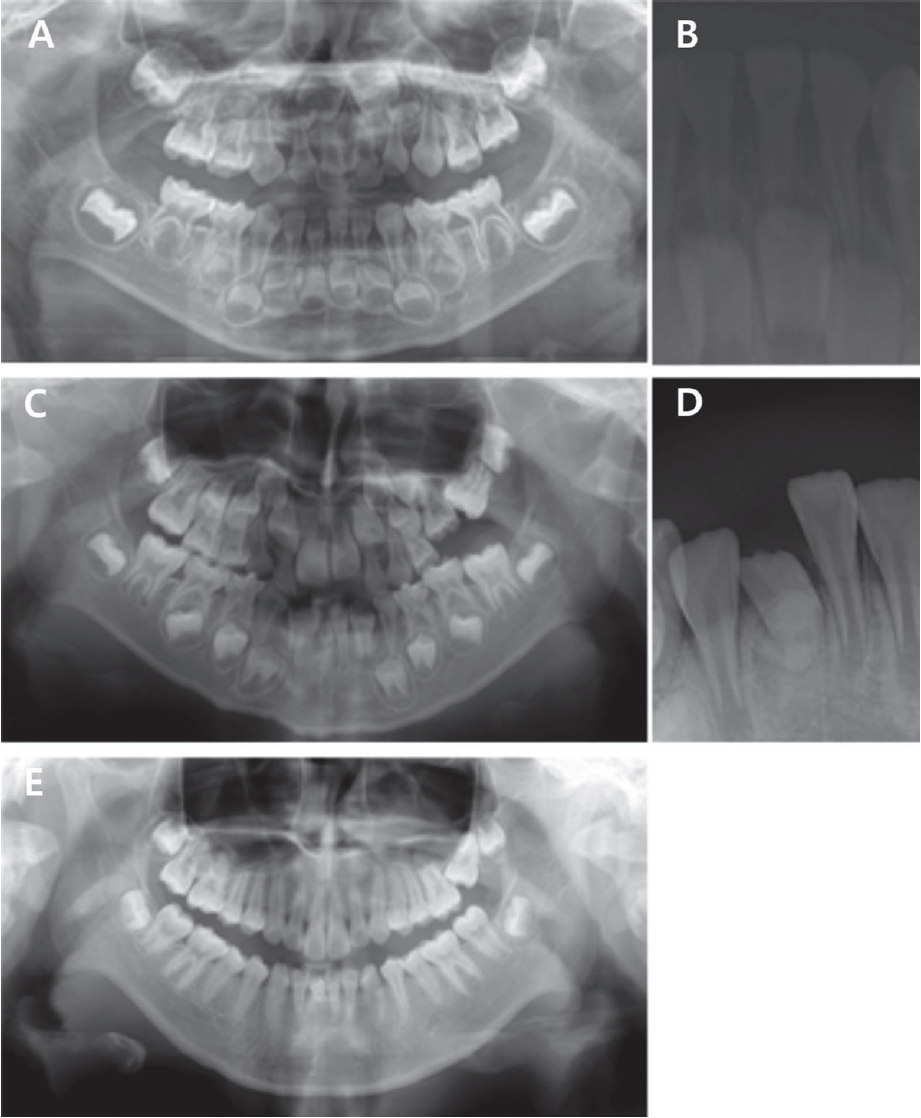

The purpose of this case report was to introduce two cases of spontaneous eruptions of dilacerated mandibular central incisors after a traumatic injury of deciduous teeth, and lead to speculations about the factors favoring spontaneous eruption.

Ōģó. Discussion

Trauma to primary teeth can lead to devastating consequences in their permanent successors, including sequestration of permanent tooth germ, partial, or complete arrest of root formation, root dilacerations, crown dilacerations, developmental disturbances of enamel, and eruption disturbances[

7]. Dilaceration of the permanent tooth is generally the result of avulsion and intrusion of their primary predecessors[

3,

8]. Dilaceration is more common in the maxilla than in the mandible and the dilacerated tooth often shows eruption disorders and hypocalcifications of the crown[

4-

6]. In both the cases described in this report, the dilacerated teeth were mandibular central incisors; and trauma to the mandibular primary central incisor was the cause of dilaceration of the permanent incisor.

The pathology of dilacerated teeth supports the theory of displacement of the enamel epithelium and the mineralized portion of the tooth relative to the dental papilla and cervical loops[

3]. When a mechanical force is applied to the primary incisor, the vertical component of the impact force is transferred in the direction of the longitudinal axis of the primary incisor; it may be transferred through the apex to the noncalcified or partially-calcified tooth germ of the permanent successor[

9]. This alters the position of the previously calcified incisal matrix, whereas it does not change the remaining apically soft matrix[

10].

The clinical appearance of this deformity is dependent on the stage of development at which the injury occurred[

11]. Malformation in the permanent successor has been reported after the intrusion of primary incisors in children between the ages of 1 and 3 years. The germs of permanent teeth are particularly sensitive in the early stages of development, between the ages of 4 months and 4 years[

12]. The formation of the mandibular permanent central incisor begins at 20 weeks of gestation. Its enamel formation begins at 3-4 months of age, and its crown formation is completed at approximately 3 years and 6 months of age[

13,

14]. In Case 1, the patient had sustained a traumatic injury to the primary mandibular central incisor at approximately 3 years of age, when the crown of the permanent successor was almost completed and showed dilaceration adjacent to the cementoenamel junction of the permanent successor. Crown dilaceration can result from the intrusion of a primary incisor at approximately 2 years of age when half of the crown is already formed[

4,

12,

15,

16]. In Case 2, the patient had sustained a traumatic injury to the primary mandibular central incisor at approximately 2 years of age when the crown of the permanent successor was being formed and showed crown dilaceration of the permanent successor.

In this cases, both the dilacerated mandibular permanent incisors erupted spontaneously, which differs from the outcomes of dilacerated maxillary teeth reported in several other studies, which often showed eruption disorders[

6,

9]. There are a few possible reasons for this discrepancy in the outcome. First, although not all factors associated with dental eruption are known, the elongation of the root and the modification of the alveolar bone and the periodontal ligament are suspected to be the most important factors[

17]. In Case 2, the dilacerated tooth showed a crown dilaceration with a relatively normal shape and orientation of the dental root; these factors were assumed to have a positive impact on the possibility of a spontaneous eruption. Second, although the patient in Case 1 showed dilaceration at the boundary between the root and the crown, tooth eruption was considered to be favorable because the tooth was dilacerated laterally, rather than labiolingually. The eruption disorders have been reported to be frequently associated with labiolingual or buccolingual dilacerations[

18]. As another plausible reason, unlike the maxilla with the palate, mandibular anterior teeth are less likely to show severe eruption disorders due to their limitation to undergo potential displacement. In both cases, the degree of dilaceration was not severe and the crown of the dilacerated tooth faced the occlusal side. Moreover, there were no significant space losses. Although the dilacerated tooth in Case 1 erupted spontaneously, it erupted later than the adjacent tooth. It is presumed that this delayed eruption was due to bone deposition above the germ of the permanent successor after the early loss of the deciduous predecessor tooth.

Enamel hypocalcification is the disruption of enamel matrix maturation[

9]. In hypocalcification, the tooth color may vary from white to yellow, but the enamel surface is usually not defective[

9]. In both patients described in this case report, the dilacerated teeth showed yellowish-brown discolorations of the crown. As the permanent mandibular incisors were located on the lingual side of the root of the deciduous tooth, the discoloration of the crown in both cases might have developed from a distortion of the ameloblastic layer induced by trauma to the deciduous tooth, such as labial deviation and intrusion, thereby leading to disruption of enamel maturation[

19,

20]. It has been reported that irrespective of the evidence of caries, a tooth with dilacerated crown might later develop pulpal necrosis, followed by inflammation, apical periodontitis and chronic abscess[

16,

21]. There is some doubt surrounding the etiological factors underlying pulpal inflammation and pulpal necrosis in dilacerated teeth. von Gool[

9] reported that all the dilacerated teeth in his study appeared to be non-vital; however he could not establish a rationale behind the non-vitality of these teeth. Some studies have demonstrated that occlusal trauma is responsible for the pathosis and the risk of pulpal and periradicular diseases, especially when the teeth are poorly aligned[

22,

23]. In another study, the authors concluded that the dilacerated crown area is free of gingiva and thus provides a suitable site for bacterial invasion[

4]. In Case 2 of the present report, the tooth with a dilacerated crown showed pulpal necrosis, possibly due to certain reasons. First, the protruded position of the tooth with a dilacerated crown might increase its vulnerability to subsequent trauma, thereby resulting in pulpal necrosis. Second, developmental disturbances of the tooth, such as hypocalcification and crown dilaceration, may enable bacterial invasion to the pulpal space, thereby leading to pulpal necrosis. Therefore, because the defective enamel and the dilacerated crown can enable the invasion of microorganisms, preventive restoration may be useful to protect the dilacerated crown and the defective enamel. To avoid potential microbial invasion when the dilacerated tooth is poorly aligned, the discolored and dilacerated portion of the crown should be removed after eruption, and a provisional restoration or prosthesis should be performed until final restoration can be achieved.

From our findings of this case report, it is suggested that when the dilacerated tooth is poorly aligned and shows hypocalcification, the discolored and dilacerated portion of the crown should be removed after tooth eruption, and a provisional restoration or prosthesis should be performed until final restoration can be achieved. In addition, it is suggested that if the mandibular permanent incisor shows a crown dilaceration or lateral dilaceration at the boundary of the crown and the root, there is a high probability of spontaneous eruption of the dilacerated tooth. Nevertheless, further studies are required to determine the mechanism underlying this eruption.

ŌģŻ. Summary

This case report has described about two patients who showed dilaceration of a permanent mandibular incisor, preceded by labial deviation, and intrusion of a preceding primary tooth. In Case 1, the permanent mandibular incisor showed dilaceration adjacent to the cementoenamel junction. In Case 2, the permanent mandibular incisor showed crown dilaceration. The specific malformed portion of the tooth germ is associated with the developmental stage at which the trauma occurred. Because the bent portion of the dilacerated tooth is formed with the defective enamel, the dilacerated tooth requires additional monitoring, and occasional preventive restoration may be necessary.

The dilacerated teeth often show some eruption disorders. But, both dilacerated teeth in this case report showed spontaneous eruption. Although additional research is necessary to explain the exact underlying mechanism, it is suggested that when the mandibular permanent incisor shows a crown dilaceration or lateral dilaceration at the boundary between the crown and the root, there is a relatively high probability of spontaneous eruption of the dilacerated tooth.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print