Ⅰ. Introduction

Skeletal maturity in growing patients is an important factor influencing the decision to start orthodontic treatment and the selection of treatment modalities[

1-

4]. Accurate determination of growth on the basis of age is difficult owing to the considerable individual differences in growth. Therefore, parameters representative of physiological age, such as sexual, skeletal, and dental maturity, are conferred greater clinical importance. Skeletal and dental maturity evaluations are mainly performed in the field of dentistry[

5,

6].

Skeletal maturity is evaluated by observing ossification, such as changes in the bone shape, density, and size, and the maturation stages of the cervical and hand-wrist bones are correlated with skeletal development during puberty[

7,

8]. Dental maturity is evaluated by measuring the degree of eruption or calcification of the teeth. Evaluation of the tooth calcification stage is used more commonly because tooth eruption is influenced by local factors such as ankylosis or early or delayed exfoliation of the primary teeth and impaction and crowding of the permanent teeth[

9].

Meanwhile, studies on the differences in the timing of skeletal growth according to the vertical facial type have been published. Nanda[

10] observed the adolescent growth spurt in the facial structures began earlier in individuals with a skeletal open bite than in those with a skeletal deep bite. Verulkar

et al.[

11] also reported that skeletal maturity tended to be delayed in individuals with a horizontal growth pattern than in those with a vertical growth pattern. In South Korea, Lee

et al.[

12] investigated skeletal maturity according to the vertical facial types of the female participants and found that skeletal maturity was greater in females with a high mandibular plane angle than in those with a low mandibular plane angle.

Studies have also investigated the relationship between the vertical facial type and the degree of tooth development, based on the assumption that there is an association between the degree of tooth development and skeletal growth. Janson

et al.[

13] and Neves

et al.[

14] reported that vertical facial types were associated with a high degree of dental maturity, whereas Jamroz

et al.[

15] reported that the difference in dental maturity according to vertical facial types was not significant.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the skeletal and dental maturity, assessed using lateral cephalograms, hand-wrist radiographs, and panoramic radiographs, in relation to vertical facial type classified based on the mandibular plane angle and sex in Korean children in the developmental stage.

Ⅳ. Discussion

Assessing the maturational status is crucial when clinical considerations are strongly based on the increased or decreased rates of remaining craniofacial growth, such as the timing and need for extraoral traction and the use of functional appliances[

11]. The facial type should be considered before orthodontic treatment planning and initiation if individuals exhibit differences in skeletal maturity depending on the anteroposterior or vertical facial types. Previous studies on facial types and skeletal or dental maturity have mainly focused on the anteroposterior facial type rather than the vertical facial type[

17,

21]. There is a scarcity of research on the relationship between the vertical facial type and skeletal and dental maturity, and most previous studies have been conducted in Western populations[

10,

13-

15]. To our knowledge, only one study investigated the relationship between vertical facial types and skeletal maturity in a Korean population, which only included Korean girls[

12]. Therefore, the present study was designed to evaluate the differences in the skeletal and dental maturity in relation to vertical facial types in Korean boys and girls aged 8 - 14 years.

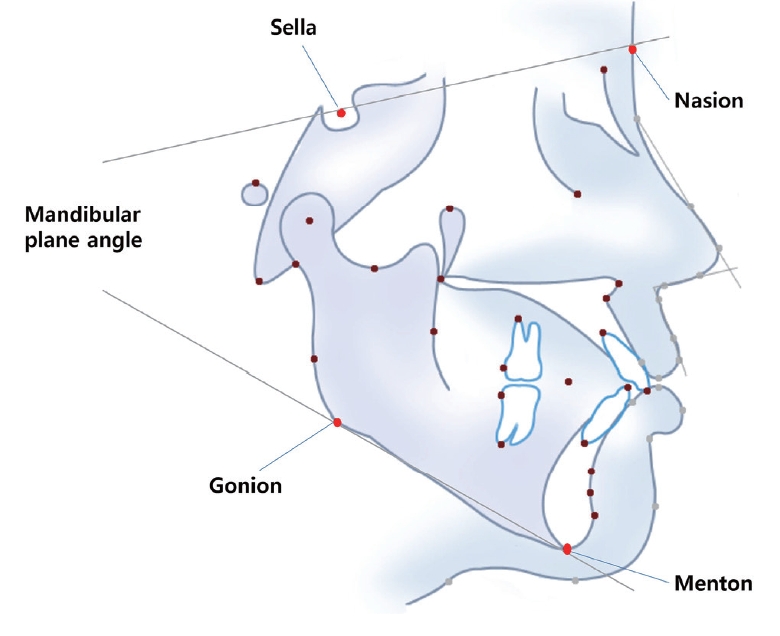

Most previous studies classified patients on the basis of the ratio of the lower anterior facial height to the anterior facial height[

10,

14]. However, in the present study, we classified the participants on the basis of the mandibular plane angle, which is a clinically simple and widely used index, as used in a domestic study[

12]. The direction of growth of the mandible affects the vertical facial type. Changes in the growth of the mandible cause forward or backward rotation of this bone, and the direction of the mandibular condyle and the rotation of the mandible are clearly related. The mandibular plane angle decreases and the mandible rotates forward in case of vertical condylar growth, causing deep bite, and the mandibular plane angle increases, and the mandible rotates backward, resulting in open bite in case of horizontal condylar growth[

22]. Thus, a low mandibular plane angle may correspond to a deep bite and horizontal growth pattern. Similarly, a high mandibular plane angle can correspond to an open bite and vertical growth pattern[

10,

13].

In the present study, the maturity of the cervical vertebrae and hand-wrist bones were evaluated. Hassel and Farmen[

4] developed a six-stage growth assessment method based on the second to the fourth cervical vertebrae, while Baccetti

et al.[

18] improvised the existing evaluation stages and proposed the cervical vertebral maturation (CVM) method, which presents five CVMS. Fishman[

19] studied the relationship between the facial growth stage and the hand-wrist growth stage and proposed SMI representing 11 stages of hand-wrist maturity. In the present study, hand-wrist maturity was evaluated using only six of the 11 SMIs in order to reduce classification errors and to accurately evaluate the growth stage[

23]. Although hand-wrist radiography is the predominantly used method for the accurate evaluation of pubertal growth spurts, other radiographic investigations are also used. Baccetti

et al.[

24] reported that the method for evaluating cervical vertebral maturity could predict the stage of mandibular growth to some extent, and Gu and McNamara[

25] reported a strong correlation between cervical vertebral maturity and the timing of maximum growth velocity of the mandible. Since lateral cephalography is used to acquire diagnostic data for orthodontic treatment, the use of cervical vertebrae for growth assessment has the advantage of not requiring additional radiography. Therefore, studies investigated whether the evaluation of cervical vertebral maturity can replace the evaluation of hand-wrist maturity. Similar to previous studies that showed a high correlation between cervical vertebral and hand-wrist maturity[

26,

27], the present study also confirmed a strong correlation between CVMS and SMI (

r= 0.832;

p < 0.001,

Table 11).

We found that hand-wrist maturity was greater in individuals with a vertical facial growth pattern than in those with a horizontal facial growth pattern. Considering the close relationship between hand-wrist maturity and the maximum growth spurt during puberty[

10,

28,

29], we may suggest that the trend in the present study was similar to that in the study by Nanda[

10], who reported that the growth spurt during puberty was faster in subjects with an open bite than in those with a deep bite. In the study of Korean girls conducted by Lee

et al.[

12], it was reported that the group with vertical facial growth pattern showed the greatest hand-wrist maturity, similar to the finding in the present study. Among other similar studies, Verulkar

et al.[

11] did not find statistically significant differences between the cervical vertebral and hand wrist maturation of the vertical and horizontal growth groups, which was not consistent with the present study. This difference could be attributed to the fact that Verulkar

et al.[

11] included 60 participants while the present study included 184 participants. Therefore, it is necessary to consider the effect of the size of the study population on the accuracy of the results, and further longitudinal studies with a uniform sample size are necessary to eliminate this effect.

With regard to skeletal maturity, girls in the normal growth group and vertical growth group showed significantly greater hand-wrist maturity. Both cervical vertebral maturity and hand-wrist maturity in the horizontal growth group showed no statistically significant difference according to sex. The age at which the radiographs were acquired can be a reason for such a result. At the time of image acquisition, boys were 4 months older than girls in the normal growth group, and 6 months older than girls in the vertical growth group, whereas boys in the horizontal growth group were 11 months older than girls (

Table 3). Thus, there was a larger difference in the timing of radiography in the horizontal growth group, which is likely to have affected the outcome.

Demirjian

et al.[

20] proposed the DI by classifying the period from the start of calcification of the tooth embryo until apical closure into eight stages, and studies that used this classification system reported a strong correlation between skeletal and dental maturity[

15,

16]. DI[

20] is based on the root shape and the relative ratio of the root to the height of the crown, so there is little distortion due to enlargement or reduction of the image[

23]. Olze

et al.[

30] reported high reproducibility in a study evaluating the maturity of the third molar using DI, and Dhanjal

et al.[

31] reported that dental maturity evaluation using DI showed high concordance among the examiners. In the present study, dental maturity was examined on the basis of the tooth age obtained using the Demirjian method[

20]. Among previous studies examining vertical growth patterns and dental maturity, Jamroz

et al.[

15] did not find a link between tooth development and the vertical skeletal morphology. In contrast, Janson

et al.[

13] reported greater dental maturity in the open bite group than in the deep bite group, and Neves

et al.[

14] and Verulkar

et al.[

11] reported that maturation of the permanent teeth occurred more rapidly in subjects with a vertical growth pattern than in those with a horizontal growth pattern, consistent with the results of this study. These discrepancies in results could be attributed to differences in the target age and classification criteria among studies. The target age groups in previous studies were 7.5 - 10.9 years[

13], 8 - 8.9 years[

14], and 9 - 12.9 years[

15], whereas the study by Verulkar

et al.[

11] and the present study attempted to reflect the effects of growth during puberty by including a wider age range of 8 - 14 years. In addition, Janson

et al.[

13] and Jamroz

et al.[

15] used the ANS-Me/N-Me ratio as a criterion for vertical growth pattern, whereas Neves

et al.[

14] classified vertical and horizontal growth pattern using SN-GoGn, SN-Gn, FH-MP, and the lower anterior facial height. On the other hand, the mandibular plane angle was used in the present study and the study by Verulkar

et al.[

11], and this may have affected the results. Therefore, we believe that additional studies with uniform participant group, age, and classification criteria are needed for accurate comparison.

When the correlation between the mandibular plane angle and the observed items was examined, there were strong correlations in the following order: CVMS, SMI, and dental age (

Table 11). Sierra[

32] showed that dental maturity shows a low tendency to correlate with other developmental ages, and that there may be a difference due to the ectodermal origin of teeth and mesodermal origin of the skeleton. Thus, the correlation of the mandibular plane angle may be stronger with cervical vertebral and hand-wrist maturity than with dental maturity.

This early maturation may be considered while planning therapies that rely on the pubertal growth spurt for achieving the best treatment outcomes, such as functional and mechanical orthopedic treatment. While determining the timing of orthodontic treatment, earlier treatment initiation may be considered for patients with a predominantly vertical facial type than for those with a predominantly horizontal facial type, because the signs of pubertal growth spurt are likely to appear earlier in children with a vertical facial growth pattern, and tooth calcification and subsequent eruption may occur earlier than children with horizontal growth patterns. This also holds true for fixed appliance therapy that depends on the eruption of the second molars during the initial stages of treatment. However, the vertical facial type is an auxiliary criterion for determining the optimal time for initiating orthodontic treatment, and additional studies must be conducted to determine certain causal and clinical applications.

This study had several limitations. First, skeletal and dental growth and development of children in the developmental stage are dynamic and continuous processes; however, the present study was conducted using a cross-sectional design. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct longitudinal studies to compare the skeletal and dental maturity with increasing age. Second, this study could not identify a clear association between vertical facial types and skeletal and dental maturity. With regard to the difference in maturity according to growth patterns, previous studies have mentioned that differences in growth pattern may be related to differences in height[

33]. Moreover, the intrinsic characteristics of each facial shape, in addition to genetic characteristics, were mentioned as a factor[

14]. However, no study has given a clear reason. To establish a clear relationship between vertical facial types and skeletal and dental maturity, cumulative research over several years is required.

Despite these limitations, our study is important since few studies have been conducted on similar topics, especially in Korea[

12], where skeletal maturity has been investigated according to vertical facial types, but only in girls and no study has been conducted on tooth maturity. Therefore, this study is meaningful because it also included boys[

12] to evaluate both skeletal maturity and dental maturity according to the vertical facial types, and additionally compared sex differences. Moreover, the study is clinically meaningful because it may also provide ancillary indicators to help determine the optimal timing of orthodontic treatment initiation. Future studies using the same criteria are needed to enable accurate comparative analysis of skeletal and dental maturity according to vertical facial types.

PDF Links

PDF Links PubReader

PubReader Full text via DOI

Full text via DOI Download Citation

Download Citation Print

Print