Strategies for the Prevention of Dental Caries as a Non-Communicable Disease

Article information

Abstract

치아우식증은 치아, 바이오필름(biofilm), 식이 요인의 상호작용을 기본으로 타액, 불소 등의 구강 환경요인과 생물학적, 행동적, 사회문화적, 유전적 요인이 관여하는 복잡한 다인성질환이다. 최근 치아우식증은 외부 병원체의 감염에 의한 것이 아닌 구강 미생물군의 생태적 변화에 따른 불균형(dysbiosis)의 결과로 이해되면서 전염성질병에서 비전염성 질병(non-communicable diseases, NCD)으로 전환되었다. 치아우식증은 심혈관질환이나 당뇨병과 같이 만성적으로 진행되는 비전염성 질환(NCD) 특성을 가지며, 식이섭취와 생활 습관과 환경적 요소들이 관여한다는 점에서 유사성이 있다. 높은 유병률과 함께 사람들의 건강과 삶의 질에 미치는 영향을 감안할 때 효과적인 구강 건강관리를 목표로 비전염성 질환(NCD)로서 치아우식증에 대한 이해가 필요하며, 구강 미생물군의 생태적 균형을 이루기 위한 적절한 예방법과 효율적인 공중보건 정책들이 제공되어야 할 것이다.

Trans Abstract

Dental caries is a multifactorial disease influenced by interactions between teeth, biofilm, dietary factors, and various biological, behavioral, sociocultural, and genetic factors. Recent research has shown that dental caries results from dysbiosis, an imbalance in the oral microbial community, shifting the concept from an infectious disease to a non-communicable disease (NCD). Dental caries shares similarities with other chronic NCDs such as cardiovascular diseases and diabetes, as they all relate to dietary intake, lifestyle habits, and environmental factors. Considering the high prevalence of dental caries and its impact on people’s health and quality of life, it is important to understand dental caries as an NCD and develop effective oral health management strategies. Ecological prevention methods and efficient public health policies should be provided to reduce risk factors associated with dental caries.

서론

치아우식증은 어린이와 성인에서 빈발하는 만성질환으로서 치아 상실에 따른 구강건강 문제를 야기하여 개인의 삶의 질에 영향을 미친다. 우리나라 보건복지부에서는 3년마다 어린이 구강건강실태조사를 실시하고 있으나 영구치 우식경험지수는 해마다 감소하다 최근 정체된 상태이며, 2018년 조사된 DMFT index가 우리나라는 1.84로서 OECD 등 선진국보다 여전히 높은 수준이다[1]. 치아우식증은 여전히 지역사회와 국가 간의 불균형으로 남아있는 것이 현실이며, 특히 열악한 교육 수준과 낮은 사회경제적 지위를 가진 사람들, 발달 장애인과 노령층 등에서 우식위험에 더욱 노출되어 있다.

세계보건기구(WHO)는 치아우식증은 병원균의 감염에 의해 유발되지 않고, 한 사람에게서 다른 사람에게 전염되지 않는 만성 질환이며, 식이 섭취, 구강건강과 관련한 신체 활동, 생활 습관 등과 관련이 있는 당뇨병이나 비만과 같은 비전염성 질환(NCD)으로 규정하고 있다[2]. 또한 비전염성질환(NCD)으로서 치아우식증의 예방 및 통제를 위한 글로벌 전략을 개발하고, 지역사회 기반 예방 프로그램, 효과적인 구강건강 교육, 건강한 식단 장려, 단 음식과 음료에 대한 접근을 제한하는 공공보건기관의 개입이 필요하며, 정기적인 치과 검진과 전문적인 치면세마 및 불소 치약과 구강청결제 사용을 권장하고 있다[3].

이에 치아우식증을 감염병이 아닌 비전염성질환(NCD)임을 이해하고, 구강 바이오필름의 조절을 위한 생태학적 예방법에 대해 알아보고자 한다.

본론

1. 치아우식증은 비전염성질환(Non-communicable disease, NCD)이다.

오랫동안 치아우식증의 병인론에 대한 연구 결과, 질환에 대한 개념이 지속적으로 변해 왔다. 과거에는 치아우식증이 병원성 박테리아에 의해 발생하는 전염성질환으로 간주되었으며, 대표적인 원인균으로서 Streptococcus mutans (S. mutans)는 출생과 함께 엄마로부터 전염되어 우식을 유발하는 박테리아로서 다른 전염성질환처럼 병원균을 제거하고, 사람 간의 전염을 방지하기 위해 노력을 기울여 왔다[4].

그러나 최근 바이오필름(biofilm) 형태로서 구강에서 다양하게 생존하던 미생물군(oral microbiome)에 과도한 당분이 공급됨에 따라 산 생성 박테리아가 우세종으로 전환되는 생태적 불균형(dysbiosis)을 일으키고, 구강내 산도(pH) 변화에 따른 치아 경조직의 탈회과정을 거쳐 치아우식증이 발생한다고 이해되고 있다[5,6].

2020년 발표된 유럽우식연구학회(ORCA)와 국제치과연구학회(IADR) 보고에서 “치아우식증은 바이오필름이 매개된, 식이 대사, 다인성, 비전염성, 역동적인 특성을 갖는 치아 경조직의 무기질이 소실되는 질환”으로 정의한 바 있다[7]. 이는 구강의 건강한 생태적 균형을 이루기 위한 바이오필름 역할의 중요성과 함께 단순한 박테리아 모델에서 박테리아, 식이, 숙주 감수성 및 구강위생 습관 등의 여러 요인들에 영향을 받는 다인자적(multifactorial) 모델로의 개념이 변화되었음을 의미한다[8].

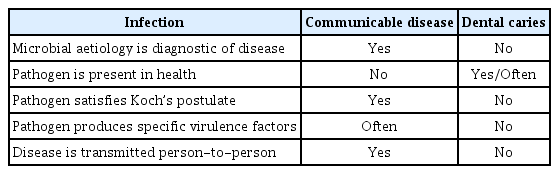

치아우식증은 비전염성질환(NCD)으로 간주된다. 왜냐하면 어느 하나의 감염 병원체에 의해 발생하지 않을 뿐만 아니라 사람 사이에서 전파되지 않는 질병으로서 환경, 생활 습관, 유전 요인이 복합적으로 작용하여 발생하기 때문이다[9](Table 1).

감염성 질환보다 오랜 기간에 걸쳐 발병하는 만성 질환으로서 치아우식증은 심혈관 질환, 암, 당뇨병, 만성호흡기 질환 등의 전신적 비전염 질환과 유사한 특성을 공유한다. 초기 우식발생에 관여하는 병원균으로서 S. mutans 는 유아기부터 가족으로부터 구강에 획득되어 건강한 사람에게 발견되기도 함에 따라 전통적인 의미에서 다른 사람에게 공기를 통해 전파되거나 감염자와 직접 접촉되어 전염되는 인플루엔자나 결핵과 같은 전염병 질환으로 분류되지 않는다. 오히려 과다한 당분 섭취, 열악한 구강 위생 습관, 숙주 감수성 및 유전 요인과 같은 위험 요인을 갖는 치아우식증은 불규칙한 식습관, 신체활동 부족, 음주와 흡연, 유전 요인 등의 위험요인을 갖는 당뇨병이나 비만과 같은 비전염성질환으로 분류하는 것이 합리적이라고 할 수 있다[10,11](Table 2).

Comparsion between general characteristics of common non-communicable diseases (NCDs) and dental caries

Koch의 가정(Koch’s postulates)은 특정 미생물이 특정 질병을 유발하는지 여부를 결정하는 기준으로서 1) 미생물은 질병의 모든 경우에 존재해야 하며, 건강한 개인에게는 존재하지 않아야 한다 2) 미생물은 순수 배양에서 분리 및 성장해야 한다 3) 미생물의 순수 배양물은 건강하고 감수성이 있는 숙주에 접종되었을 때 동일한 질병을 유발해야 한다 4) 미생물은 접종된 질병 숙주로부터 재분리되고, 원래 미생물과 동일한 것으로 식별되는 것이다[12].

치아우식증이 미생물의 인과관계에 대한 일련의 기준이 되는 Koch의 가정을 모두 충족하기는 어렵다. 즉, 질병의 모든 경우에 원인 미생물이 기본적으로 존재해야 하지만 S. mutans와 Lactobacillus 종은 모든 우식 병소에 항상 존재하는 것은 아니며, 구강에 존재한다 해도 전염력이 부족하고, 당분 섭취와 같은 위험 요인이 중요한 역할을 하기 때문이다. 또한 우식성 박테리아가 개체에서 분리 및 배양될 수 있지만 반드시 질병을 유발하지는 않으며, 감염원의 전파에 대한 증거 부족, 역학적 기전과 함께 복잡한 다인자성 원인요소들이 관여한다는 점에서 전염성 질환보다는 비전염성 질환의 특성을 가진다고 할 수 있다[13-15].

심혈관 질환, 암, 호흡기 질환 및 당뇨병으로 인해 연간 4천만 명 이상이 사망하는 비감염성 질환(NCD)은 질병 총 부담의 약 80%를 차지하여 엄청난 경제적 비용과 공중보건 문제를 초래하는데 잘못된 식이 습관, 음주 및 흡연, 영양실조, 낮은 신체 활동과 함께 심리적, 사회적, 문화적, 경제적 요인과 밀접하게 관련되어 있다[16,17].

2019년 세계보건기구(WHO) 총회 이후 치아우식증을 심혈관질환, 암, 그리고 당뇨병과 같은 비전염성 질환(NCD)으로 분류하였는데 한 사람에게서 다른 사람에게 직접 전염되지 않는다는 증거와 일치하는 분류 시스템에서 따른 것이다[18]. 비전염성 질환(NCD)으로 인해 세계적으로 매년 4,100만 명이 사망하고 있는데 이는 전체 사망자의 74%에 해당하며, 심혈관 질환, 암, 만성호흡기질환 및 당뇨병 순으로 저소득 국가에서 대부분 발생된다[19].

치아우식증은 치아 손실의 주요 원인이므로 그 결과로써 기능적 심미적 회복을 위한 경제적 부담이 증가하고, 전신건강에 영향을 미친다. 치아우식증을 포함한 치주질환은 심장질환 및 뇌졸중과 같은 심혈관 질환과 관련이 있으며, 당뇨병 발생 위험을 증가시키거나 악화될 수 있다고 하였다[20]. 또한 호흡기 감염위험이 증가하고, 임신 합병증, 알츠하이머병과 같은 인지장애를 유발할 수 있는 가능성이 제시되었는데 향후 구강건강과 전신 비감염성 질환(NCD)을 연결하는 근본적인 메커니즘에 대한 연구가 필요하다[21].

2. 치아우식증은 바이오필름 매개 질환(Dental biofilm-mediated disease)이다.

우리 인체의 정상 세균(normal flora)인 대부분의 미생물은 해로운 병원체로부터 우리 몸을 방어할 수 있는 보호기능을 한다. 즉, 인체는 미생물에게 서식 장소와 영양분을 제공하고, 미생물은 면역체계를 지원하며, 음식의 소화 및 대사 과정에서 중요한 역할을 하는 유익한 상생적 관계를 유지한다[22,23].

구강에는 700종 이상의 미생물이 다양하게 존재하며, 생존을 위한 공동체(consortium)를 형성하는데 이 중 치아우식증과 관련이 있는 바이오필름은 치아 표면에 고착하여 생존하는 박테리아 집단이다. 바이오필름은 분비된 세포외 다당류(extracellular polymeric substance, EPS) 매트릭스에 의해 보호, 접착, 안정화되어 영양소를 제공받는다[24]. 바이오필름 대부분은 물(91%)로 구성되고, 나머지는 5% 미생물, EPS 2%와 DNA, RNA, 단백질 순이다[25].

미생물이 타액 등에 부유하는 방식이 아니라 단단한 치아 표면이나 점막에 부착하는 바이오필름은 나름의 유리한 생존방식이기 때문이며, 복잡하고 고도로 분화된 공동체를 형성한다. 박테리아를 보호하는 장벽 역할로서 기계적 힘이나 항균제에 대해 저항성이 500배 이상 증가된다고 하니 개별적으로 부유하지 않고 바이오필름을 형성하는 이유를 알 수 있다[26].

치아의 표면에서 바이오필름의 형성 과정은 1) 법랑질 표면의 단백질과 획득막(pellicle)에 초기 박테리아의 부착 2) 세포 외 다당류(EPS) 합성에 의한 박테리아 증식 3) 바이오필름 성숙 과정을 통한 복잡한 3차원 구조 발달 4) 바이오필름 분산 등이다[27,28]. 바이오필름이 증식되어 클러스터 형태가 되면 영양공급 통로를 통해 영양분이 공급되고, 쿼럼 센싱(quorum sensing) 메커니즘으로 정보를 교환하면서 유전자 발현 패턴을 변경하여 환경 변화에 적응한다[29].

바이오필름은 인체를 구성하는 치아, 위장관, 기관지, 비뇨기관 등에서 형성되면서 만성 감염이나 염증성 질환을 일으키는데 전체 감염질환의 80%가 바이오필름이 매개되어 발생한다. 구강 바이오필름 관련 치과 질환은 치아우식증을 비롯한 치주 질환, 구취, 캔디다 감염증 등이 있다[30].

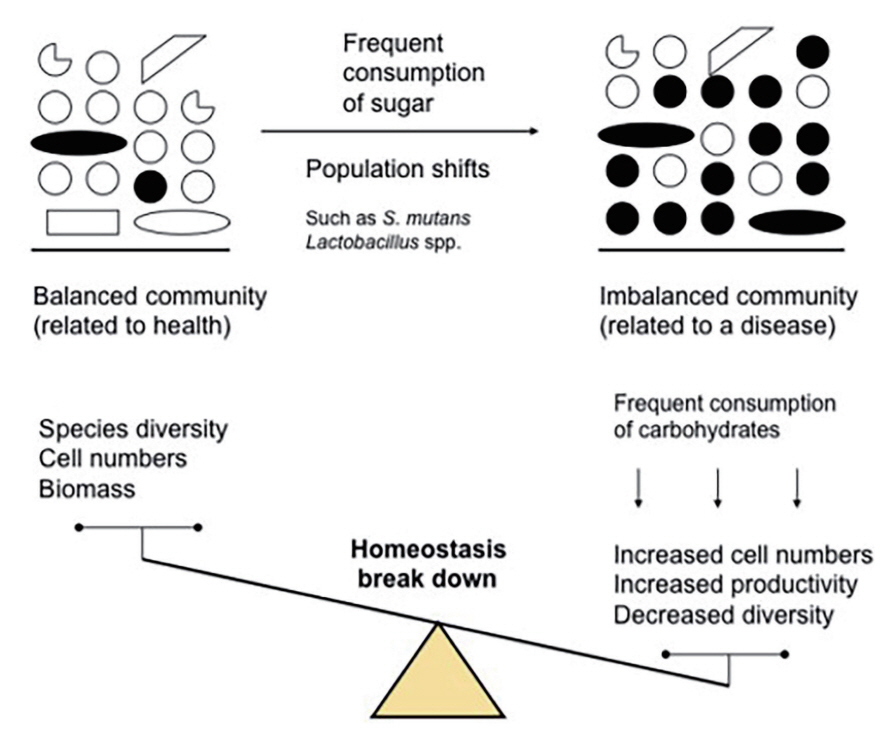

생태 치태 가설(Ecological plaque hypothesis)은 정상적으로 상주하는 미생물군에서 병원균이 우세종으로 전환되어 생태적인 불균형(dysbiosis) 때문에 치아우식증이 발생된다고 주장하는 이론이다[31]. 즉, 과다한 당분 공급 때문에 산성화된 구강환경으로 생태적인 변화(ecological change)가 먼저 시작되고, 구강내 상주균이 S. mutans , S. sobrinus , Lactobacillus종과 같은 산 생성 박테리아로 교체되는 생태적 이동(ecological shift)이 일어남으로써, 지속된 산성 환경으로 치아가 탈회되어 우식병소가 발생하게 된다는 것이다. 이와 같이 생태적 변화를 주도하는 당분 섭취를 제한 또는 억제해야 하는 것이 중요한 이유가 된다[32,33](Fig. 1).

The starting point for harming the ecological stability of the oral microbiota is frequent sugar intake, and acid-producing bacteria such as S. mutans and Lactobacillus species are converted to the dominant species, leading to an imbalance in the oral ecosystem, resulting in dental caries.

박테리아의 대사산물로서 산의 생성과 세포외 다당류(EPS) 증식은 생태적 이동(ecological shift)을 통한 구강 미생물군의 분포가 달라지게 된다. 구강내 박테리아는 Streptococcus, Actinomyces, Veillonella, Neisseria 및 Haemophilus 종 등으로 다양하게 구성되는 것이 정상이나 생태적 환경변화에 의해 S. mutans, S. sobrinus , Lactobacillus, Actinomyces 종 등 소수로 존재하던 우식병원성 박테리아로 대체되는 것이다[34]. S. mutans , Lactobacillus 종과 같은 산을 생성하는 병원균들의 우세는 타액의 산도를 더욱 낮추게 되고, 결국 법랑질 무기질의 탈회 과정으로 진행됨에 따라 우식병소가 발생하는 것이다. 정상 구강 환경에서 전체 미생물의 약 1 - 2%로 구성되던 S. mutans 와 Lactobacillus균이 포도당 공급 이후 pH 4에서 55%로 급속히 증가를 나타내는데 이는 낮은 산성 환경에서 내산성이 강한 박테리아가 주류를 이루며 생존함을 알 수 있다[35].

산성화된 구강 환경은 무기질이 손실되는 탈회(demineralization)와 타액의 완충능력에 따른 재석회화(remineralization)가 서로 평형을 이루는 역동적인 과정이며, 산생성과 내산성 단계를 거쳐 무기질 손실이 더 많이 진행됨에 따라 우식 병소가 발생한다. 내산성이 강한 뮤탄스 연쇄상구균(mutans streptococcus, MS)의 수에 비례하여 치아 경조직의 무기질 손실이 증가되기 때문에 반대로 무기질 획득에 유리한 비MS와 방선균(Actinomyces)과 같은 박테리아로 바이오필름이 구성된다면 무기질의 동적 안정성을 얻는 데 더욱 유리한 조건이 된다[36,37].

최근 생태계에서 중요한 역할을 하는 병원체(keystone pathogen)가 다른 박테리아의 생태학적 역할을 조절할 수 있다는 가설에 따르면 치아우식증의 경우 S. mutans 가 다른 산생성 박테리아의 성장을 촉진하여 구강 미생물군의 불균형을 초래하는 핵심 병원체로 판단된다. 구강 미생물군에서 핵심 병원체가 적은 수로 존재함에도 불구하고 생태적 변화의 연쇄반응을 유발할 수 있는 영향력은 훨씬 크기 때문에 반드시 다수가 존재할 필요는 없다는 것을 의미한다[38,39].

치아우식증의 병인론의 변화와 함께 바이오필름과 숙주(host)인 치아, 그리고 환경요인 사이의 복잡한 상호작용에 대한 이해가 필요하고, 구강 미생물군의 생태적 균형의 중요성이 더욱 강조되고 있다. 발효성 탄수화물의 빈번한 섭취와 열악한 구강 위생 습관과 같은 위험 요인들이 구강 미생물군의 생태적 불균형이 결과로써 발생하는 치아우식증은 바이오필름이 매개된 질환임이 분명하다.

3. 치아우식증 예방을 위한 생태적 접근(Ecological approach to prevention of dental caries)

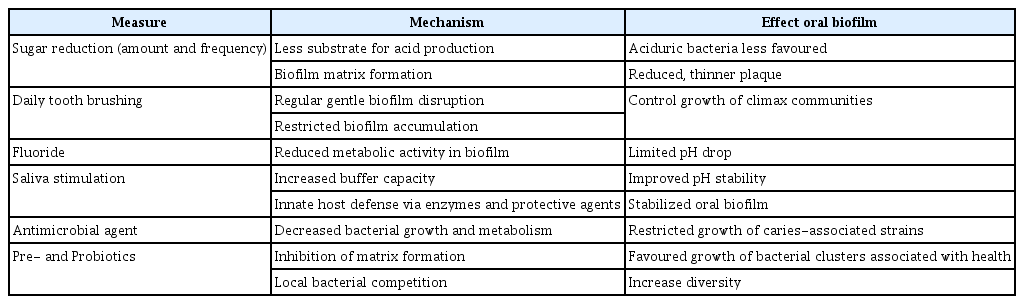

구강 바이오필름의 생태적 균형을 유지하거나 복원하기 위하여 당분 공급의 제한과 칫솔질을 통한 구강위생 관리가 필수적이며, 항균제, 불소의 사용, 타액 강화 등의 예방적 전략이 필요하다[40](Table 3).

1) 당분섭취 제한(Sugar reduction)

구강 미생물군 불균형의 주요 원인인 빈번한 당분 섭취를 줄이는 것을 치아우식증의 예방을 위한 가장 효과적인 방법이다. 당분이 공급되면 생태적 변화가 시작되는 산 생성이 유발되기 때문이며, 당분섭취 제한을 통하여 산성 대사산물의 감소와 바이오필름을 구성하는 매트릭스 구조를 약화시킬 수 있다[41].

세계보건기구(WHO)는 치아우식증을 비롯한 비전염성 질환(NCD)의 발생 위험을 줄이기 위해 총 에너지 섭취량의 10% 미만, 이상적으로는 5% 미만으로 유리당(free sugar) 섭취를 제한할 것을 권장하였다[42]. 유리당은 가공 과정에서 식품 및 음료에 첨가되는 단당류와 이당류와 꿀, 시럽, 과일주스에 자연적으로 존재하는 당류로서 유리당 섭취를 줄이는 것을 우식 예방을 위해 우선해야 한다.

개별적으로 일상생활에서 단 음료수 대신 물이나 우유를 선택하고, 설탕이 첨가된 식품 라벨을 확인하여 유리당이 첨가된 음료나 식품의 섭취를 제한해야 한다. 또한 탄수화물의 지속적인 공급이 결국 병원균의 활동을 개시하기 때문에 개인별 우식 위험도를 평가함으로써 우식성 식품을 줄이고, 건강한 식이 습관을 갖도록 어린이와 보호자에게 강조되어야 한다[43].

설탕의 대체제로서 자일리톨(xylitol)과 같은 비발효성 감미료를 사용한다면 우식성 병원균에 의한 산 생성이 억제되어 바이오필름 형성이 감소되는 효과를 나타내는데 주로 치아 맹출 중인 어린이, 우식 고위험군 그리고 타액건조증 환자에게 추천된다[44]. 자일리톨을 사용시 뮤탄스 연쇄상구균(MS)의 감소, 산 생성 억제, 타액 흐름의 증가에 따른 재석회화효과 등의 항우식작용에 대한 많은 연구가 시행되었다. 자일리톨은 우식예방에 효과적일 수 있지만 적절한 양을 사용하여야 하고, 정기적인 위생관리를 병행해야 한다[45].

이미 널리 공급되고, 상업적으로 광고되는 설탕 소비에 대해 어린이와 성인에게 건강한 선택을 하도록 요구하는 것은 어려운 일이다. 따라서 다른 감염성질환(NCD)과 같이 치아우식증에 대한 당분 섭취 감소에 대해서 개별적인 생활 습관 개선과 함께 사회적 측면을 해결할 수 있는 공중 보건정책이 필요하다. 학교나 지역사회에서 시행할 수 있는 공공 정책으로서 어린이에게 설탕 마케팅 금지, 건강식품 접근성 향상, 가공식품 표시제와 설탕 과세 등의 포괄적인 프로그램이 소개되고 있다[10,46].

2) 구강위생 관리(Oral hygiene)

칫솔질은 치아의 바이오필름 형성을 방지하고, 양호한 구강 위생을 유지하는 가장 효과적인 방법 중의 하나이다. 양치질을 통하여 음식물 찌꺼기를 제거하여 구강 내 박테리아에 영양 공급원의 제공을 방지하고, 치아 표면에 부착된 바이오필름을 기계적으로 제거할 수 있으며, 잇몸 마사지 효과로서 건강한 치은 조직을 유지할 수 있다. 규칙적이고 부드러운 칫솔질을 통하여 치아 바이오필름을 조절함으로써 건강한 구강 생태계를 유지하고, 칫솔이 효과적으로 닿지 않는 부위는 치실의 사용을 추천한다[47,48].

규칙적인 하루 2회 이상의 칫솔질을 통하여 구강 미생물군이 유익한 상태로 유지될 가능성이 높으며, 불소함유 치약의 동반 사용은 바이오필름 조절 및 관리에 더욱 효과적이다[49].

3) 항균제(Antimicrobial agent)

치아우식증 유발 미생물군에 대한 항균제의 사용은 광범위하게 연구되었으며, 대표적 항균제로서 클로르헥시딘(chlorhexidine)은 뮤탄스 연쇄상구균(MS)을 효과적으로 감소시키는 것으로 알려졌다. 그러나 장기간 사용 시 새로운 내성 균주의 출현이 우려됨에 따라 클로르헥시딘이 함유된 구강 세정제는 구강 위생 상태가 매우 좋지 않거나 구강 건조증이 심하여 우식 고위험군에게 단기간으로 제한적 사용이 추천된다[50,51]. 또한 항균성을 가진 에센셜 오일(essential oil)은 구강 세정제와 치약에 사용되기도 하는데 장기간 사용에 대한 효과와 안전성에 대한 더 많은 연구가 필요하다[52,53].

최근 항균 펩타이드(antimicrobial peptides, AMP)는 박테리아 세포막을 파괴하고, 세포벽 합성을 억제하여 S. mutans를 포함한 다양한 박테리아에 대해 광범위하게 항균 활성을 타내는 것으로 밝혀졌으나 AMP의 작용 메커니즘과 안전성에 대해 더 많은 연구가 필요하다[54,55]. 또한 미생물의 신호물질 전달시스템인 쿼럼센싱(quarum sensing, QS)의 기능을 방해하기 위해 개발된 쿼럼센싱 억제제(QS inhibitor)는 박테리아 간의 통신을 방해하거나 자가 유도체 효소를 분해하는 방법을 통해 바이오필름의 형성을 감소시킬 수 있다고 보고되었으며, 이러한 새로운 접근방식의 효과와 안전성에 대한 연구가 필요하다[56,57].

4) 불소(Fluoride)의 사용

불소는 법랑질의 재광화를 촉진하고, 잠재적으로 우식을 유발하는 박테리아 대사를 억제한다. 불소의 항균 효과는 세포 내 효소를 억제하며, 불화수소의 형태로 세포막 수소이온 투과도를 증가시켜 박테리아 대사를 방해함으로써 산 생성을 감소시키고, 바이오필름 형성을 억제한다고 알려져 있다[58-60].

불소의 항우식 효과는 잘 알려져 있으나 우식위험도가 높은 어린이의 경우 불소만을 사용하여 치아우식증을 완전히 예방하기에는 충분하지 않은 것도 사실이다. 따라서 개개인의 우식 위험도(caries risk)를 평가하여 다양하게 적용되어야 하며, 불소함유 치약의 사용을 기본으로 6세 미만의 어린이에게 불소 용액 양치나 불소 젤 보다는 불소 바니쉬(Varnish) 형태의 사용을 권장한다[61,62].

질산은(silver nitrate)과 불소(fluoride)가 결합된 Silver diamine fluoride (SDF)의 사용은 2014년 FDA에서 상아질민 감성 치료를 위해 승인되었으나 우식병소의 진행 억제를 위해서도 사용된다. 38% SDF가 시판되는데 25%은(silver) 성분이 항균제 역할을 하고, 5% 불소는 고농도로서 법랑질의 재광화를 촉진하는 것으로 알려져 있다[63]. 치과의사는 환자나 보호자에게 부작용으로 치은 연조직자극과 착색(black stain)에 대해 설명해야 하며, 행동조절이 어려워 치료를 거부하는 우식 고위험군 어린이나 장애 환자에게 일시적 우식 정지 효과를 위해 사용할 것을 추천한다[64].

5) 타액 강화(Salivary enhancement)

구강내 타액이 풍부하게 생성되면 타액의 완충능력을 통해 산이 중화되고, 무기질을 이용한 법랑질의 재광화, 음식물 자정 작용, 함유된 효소에 의한 박테리아의 성장억제 등의 항우식 효과를 이용할 수 있기 때문에 타액 강화는 구강건강을 유지하는 데 중요한 역할을 한다[65].

무설탕이나 자일리톨이 함유된 껌을 씹으면 타액 생성을 자극할 수 있고, 정기적으로 식수로 수분을 유지하면 타액 생성을 촉진하는 데 도움이 된다. 또한 만성적 구강 건조증으로 우식 발생 위험이 높은 경우 타액 대체물 또는 인공 타액제품을 권장한다[66].

6) 프리바이오틱스와 프로바이오틱스

프리바이오틱스(prebiotics)는 구강 내 유익한 박테리아의 성장을 선택적으로 촉진할 수 있는 소화되지 않는 탄수화물이며, 프로바이오틱스(probiotics)는 유해 박테리아의 성장을 직접적으로 억제하고, 건강한 구강 미생물군을 유지할 수 있는 살아있는 미생물을 의미한다[67].

프리바이오틱스는 선택적으로 Lactobacillus와 Bifidobacterium 종과 같은 유익한 박테리아의 성장을 촉진하여 구강 미생물군의 건강한 균형을 회복하고 유지하는 데 도움을 줄 수 있다. 대표적인 프리바이오틱스로서 아르기닌(arginine)이 사용되는데 구강의 산성 환경을, 암모니아를 지속적으로 생성, 산도를 증가시켜 중성 환경으로 유도하여 S. mutans의 성장을 억제하는 효과가 입증되었으며, 현재 아르기닌이 함유된 치약 제품이 시판되고 있다[68,69].

프로바이오틱스는 S. salivarius 와 Lactobacillus reuteri 같은 유익한 박테리아를 공급하여 유해 박테리아를 밀어내고, 우식병원균에 의해 생성된 산을 중화함으로써 구강 미생물군의 균형을 유지하는 데 유용하게 활용할 수 있다. 프로바이오틱스 역시 구강 건강에 긍정적인 영향이 보고되고 있으나 작용 메커니즘과 사용 기준에 대한 더 많은 연구가 필요하다[70,71].

결론

최근 치아우식증은 감염원의 부족, 개인의 위험 요인과의 연관성, 사람과의 직접적 전파에 대한 제한 등의 증거와 함께 비전염성 질환(NCD)으로 분류되고 있으며, 치아우식증은 바이오 필름이 매개된 질환으로서 당분의 과다 섭취에 따른 구강 미생물군의 생태적 불균형의 결과로써 이해되고 있다. 구강 생태계의 균형과 회복을 위한 치아우식증 예방법으로서 당분 섭취 감소, 칫솔질을 통한 구강 위생 관리, 항균제, 불소의 사용, 프로바이오틱스 등이 널리 활용되고 있으며, 치아우식증이 구강 건강과 삶의 질에 미치는 영향을 고려할 때 학교 교육프로그램과 지역사회의 공중보건정책 개발과 지원이 더욱 강화되어야 한다.

Notes

Conflict of Interest

The author has no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.